There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Introduction

In the concrete jungles of our modern cities, a disconnect from the natural world has become an almost inevitable byproduct of urban living. We spend our days in climate-controlled environments, surrounded by artificial light and surfaces, with limited exposure to the vital elements that have shaped human evolution. This estrangement, however, comes at a cost. A growing body of scientific evidence reveals a profound link between our connection to nature and our physical, mental, and emotional well-being. This is where biophilic design emerges, not merely as an aesthetic trend, but as a science-backed approach to weaving nature back into the fabric of our urban environments, creating healthier, happier, and more sustainable cities.

This blog post explores the science behind biophilic design and its potential to enhance the quality of life for urban residents.

What is Biophilic Design?

What is Biophilic Design?

The term "biophilia," meaning "love of life or living systems," was popularized by biologist E.O. Wilson in his 1984 book describes it as the “urge to affiliate with other forms of life,” suggesting that humans have evolved with a deep-seated need for contact with natural systems. He posited that humans possess an innate, genetically determined tendency to affiliate with nature and other life forms. Biophilic design is the practical application of this concept, aiming to incorporate natural elements, patterns, and processes into the built environment. It seeks to satisfy this fundamental human need by creating spaces that foster a sense of connection and well-being.

The foundation of biophilic design is the biophilia hypothesis. The hypothesis states that humans have an innate, genetically-based affinity for the natural world and that this affinity is essential for our physical, mental, and emotional well-being.

Building on this, architect and social ecologist Stephen Kellert formalized six core principles of biophilic design that provide a practical framework for embedding nature into built environments:

1. Environmental Features: Direct inclusion of natural elements such as sunlight, water, vegetation, air, and natural materials like wood and stone create more compelling and pleasant spaces. These can be applied on various scales from potted plants indoors to large living walls or water features.

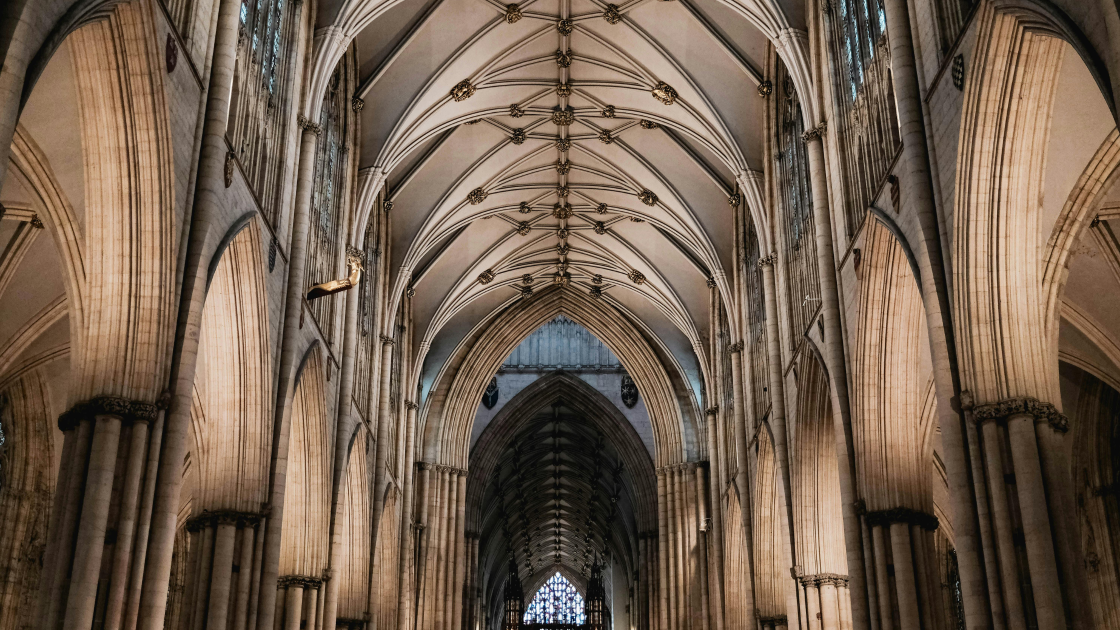

2. Natural Shapes and Forms: Utilizing organic shapes found in nature—like spirals, arches, curves, and fractals—establishes symbolic and emotional connections that feel intrinsically comforting. For example, vaulted ceilings or archways evoke shelter akin to a cave, nurturing feelings of refuge and safety.

3. Natural Patterns and Processes: Reproducing environmental rhythms like seasonal changes, light fluctuations, or water cycles within a design can reinforce our awareness and attunement to natural time scales.

3. Natural Patterns and Processes: Reproducing environmental rhythms like seasonal changes, light fluctuations, or water cycles within a design can reinforce our awareness and attunement to natural time scales.

4. Light and Space: Incorporation of natural light, open spaces, and varied spatial compositions encourages circulation and mimics the complexity of natural habitats.

5. Place-Based Relationships: Including elements unique to the local ecosystem or landscape strengthens community identity and ecological awareness.

6. Evolved Human-Nature Relationships: Acknowledging our evolutionary heritage by designing environments that support inherent human needs like prospect (wide views) and refuge (protected spaces) enhances well-being.

These principles collectively move beyond merely adding plants to spaces; biophilic design is a holistic integration of nature’s forms, processes, and sensory stimuli to meaningfully reconnect people with living systems

The science behind biophilia rests on several pathways that influence human experience in spaces:

some of the key scientific principles that underpin biophilic design:

1. Stress Reduction and Restoration

One of the most well-documented benefits of nature exposure is its ability to reduce stress. This phenomenon is often explained by the Attention Restoration Theory (ART), proposed by Rachel and Stephen Kaplan. ART suggests that our directed attention, which is crucial for complex cognitive tasks, becomes fatigued through constant use. Natural environments, with their "soft fascination," allow our directed attention to rest and recover. This is because nature offers elements that engage our attention effortlessly, without demanding cognitive effort.2. Cognitive Function and Creativity

Beyond stress reduction, nature exposure has a positive impact on cognitive functions such as attention, memory, and problem-solving. The restorative effects of nature, as described by ART, directly contribute to improved cognitive performance. When our minds are less burdened by stress and fatigue, we are better able to focus, learn, and think creatively.

3. Mood Enhancement and Emotional Well-being

Nature has a profound impact on our emotional state, lifting our spirits and fostering feelings of happiness and contentment. This connection is often linked to the release of neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, which are associated with pleasure and well-being.

Sense of Awe and Wonder: Experiencing natural phenomena, such as a dramatic sunset or a majestic mountain range, can evoke feelings of awe, which have been linked to increased happiness and a greater sense of connection to something larger than oneself. Biophilic design aims to capture these awe-inspiring moments within urban settings.

Sense of Awe and Wonder: Experiencing natural phenomena, such as a dramatic sunset or a majestic mountain range, can evoke feelings of awe, which have been linked to increased happiness and a greater sense of connection to something larger than oneself. Biophilic design aims to capture these awe-inspiring moments within urban settings.

4. Physical Health and Immunity

The benefits of biophilic design extend to our physical health. Exposure to natural light, for instance, is crucial for regulating our circadian rhythms, which impacts sleep quality and overall health. Furthermore, certain natural elements can even boost our immune systems.

Biophilic Design Elements in Urban Living Spaces

| Scale | Biophilic Design Examples | Benefits |

| Interior Spaces | Use of natural light, indoor plants, water features, natural materials (wood, stone) | Enhances mood, reduces stress, improves air quality |

| Building Architecture | Curved structural forms, natural ventilation patterns, green roofs, living walls | Supports thermal comfort, visual complexity, and biodiversity integration |

| Urban Planning | Pocket parks, green corridors, ecological restoration zones, water bodies integrated into plazas | Promotes biodiversity, social cohesion, climate regulation |

| Neighborhood Scale | Walkable spaces oriented toward nature views, community gardens, biophilic street furniture | Encourages physical activity and community interaction |

Integrating Biophilic Design for Sustainable and Healthy Cities

Biophilic design aligns closely with sustainability goals. By honoring ecological relationships and integrating living systems within urban infrastructure, cities can become not only more pleasant for humans but also better ecological habitats.

Michael Hough and other biourbanism scholars emphasize that biophilic urban design must go beyond token greenery by embedding naturalistic dimensions, spatial wholeness, and geometric coherence to support social inclusion and complex human–nature interactions

Challenges and Considerations

While the benefits of biophilic design are well-documented, there are also some challenges and considerations to keep in mind:

Conclusion

The science behind biophilic design provides a compelling case for its integration into urban living. By reconnecting people with the natural world, biophilic design has the potential to improve physical and mental health, enhance environmental sustainability, and create more livable and resilient cities. As urban populations continue to grow, the implementation of biophilic design principles will be crucial in shaping the cities of the future.

Dr. Anand Bafna

Herbalist. Pharmacist. Naturopath